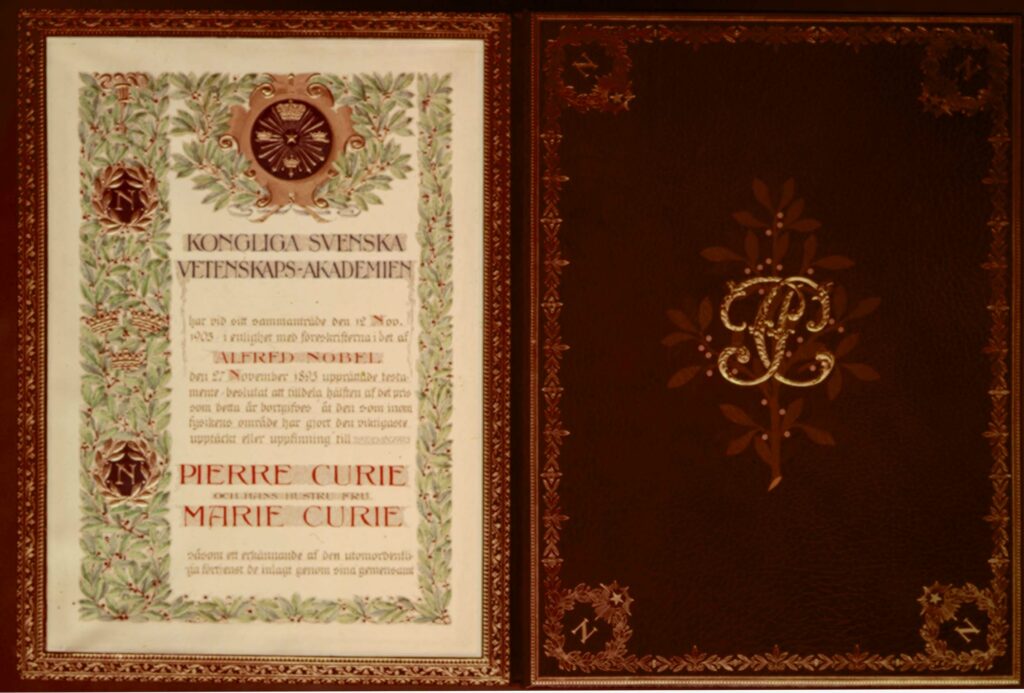

The 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics

Auteur : Loic Barbo

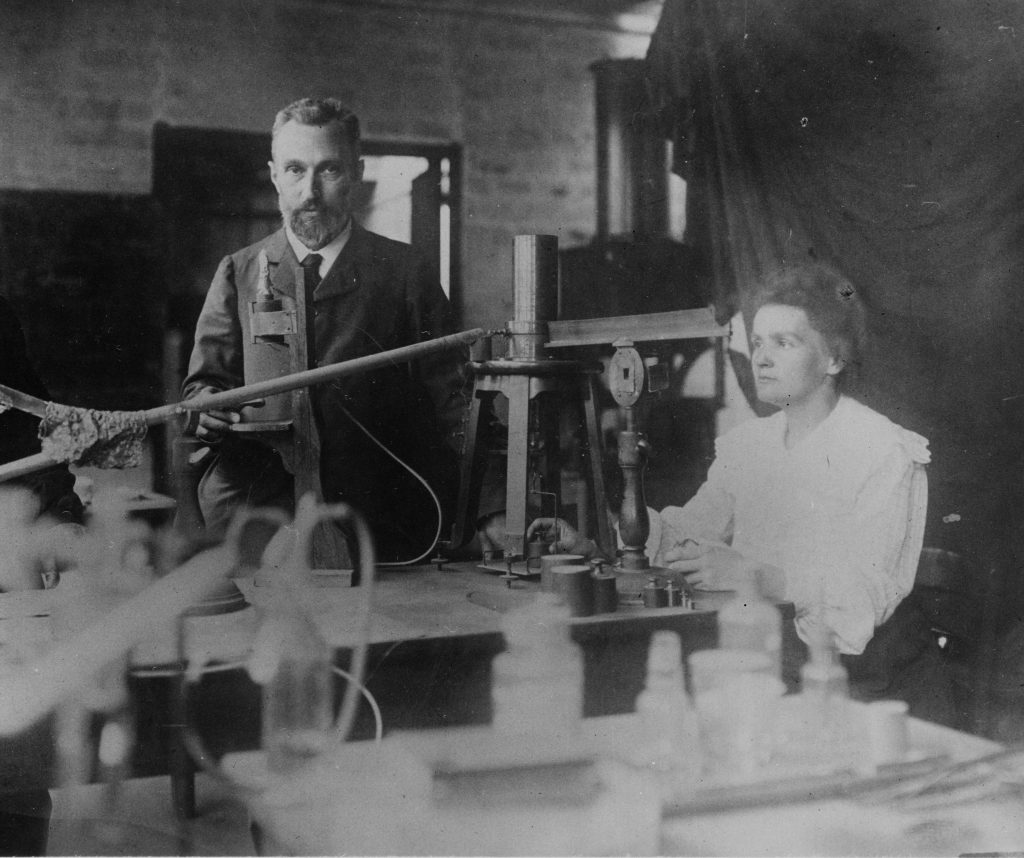

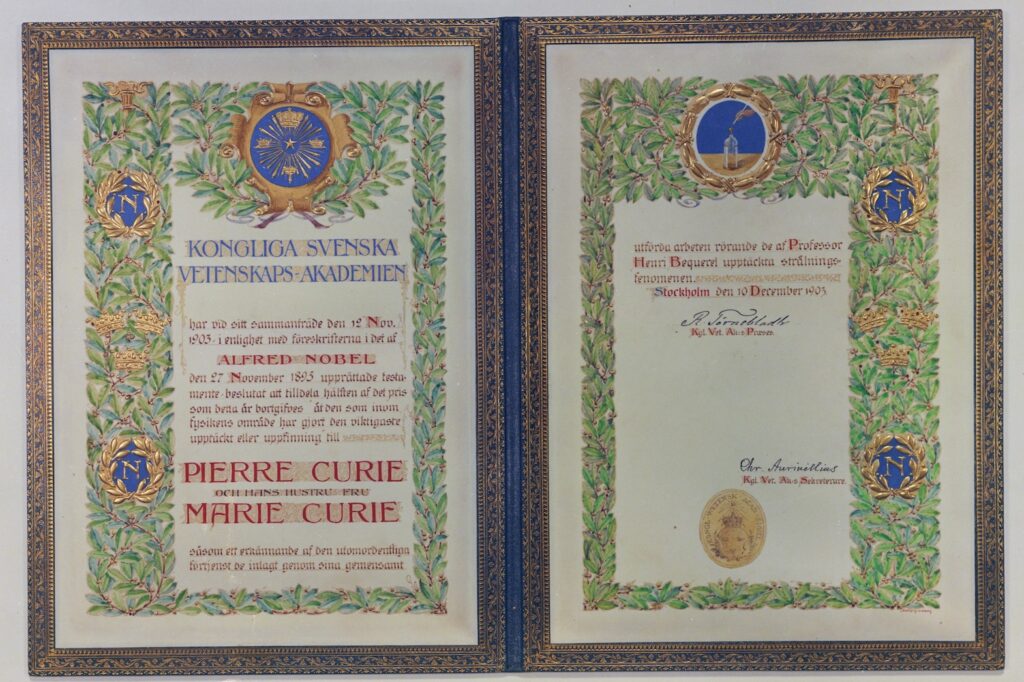

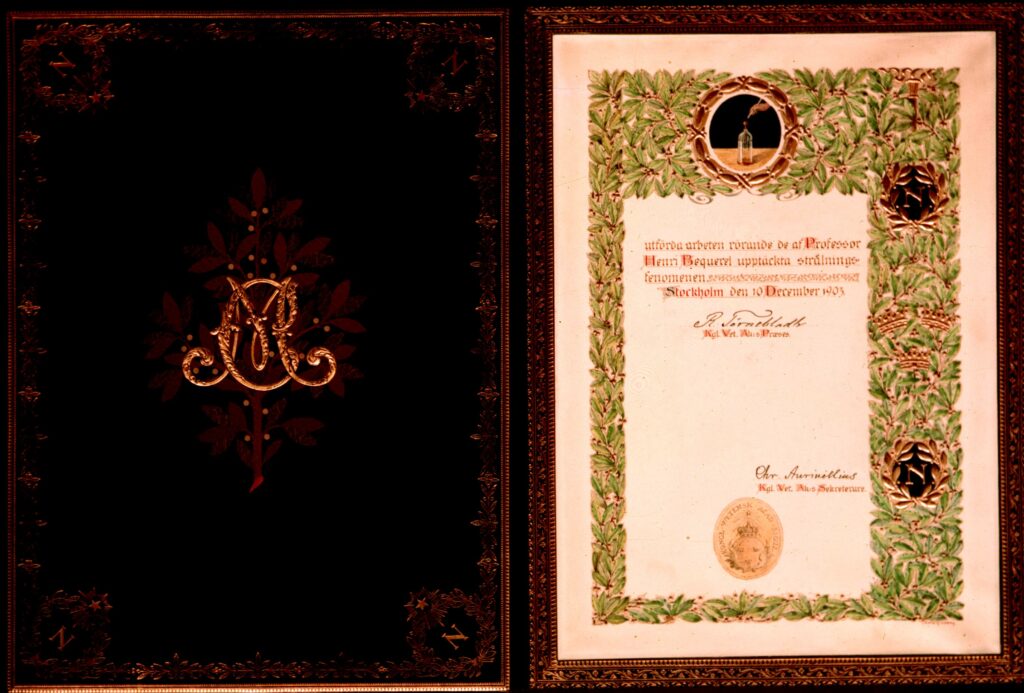

On November 14, 1903, Pierre and Marie Curie received a letter from Professor Carl Aurivillius, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy of Sciences.

“Mr. and Mrs. Curie,

As I have already had the honor of informing you by telegram, the Academy of Sciences, in its session of November 12, has decided to award you half of this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics.

On December 10, during the formal general assembly, the decisions — which must remain strictly confidential until then — of the various prize-awarding committees will be announced, and during the same occasion the diplomas and gold medals will be presented.

On behalf of the Academy of Sciences, I hereby invite you to kindly attend this assembly to receive your prize in person. In accordance with Article 9 of the Nobel Foundation statutes, you are required to give a public lecture in Stockholm related to the awarded work, within six months of the ceremony.1”

Pierre Curie responded on November 19, and after thanking the Swedish Academy of Sciences, requested a postponement of the ceremony and the lecture.

“Mr. Permanent Secretary,

We are very grateful to the Academy of Sciences of Stockholm for the great honor it bestows upon us by awarding us half of the Nobel Prize in Physics. We kindly ask you to convey to the Academy our deepest thanks and appreciation.

It is very difficult for us to travel to Sweden for the December 10 ceremony. We cannot be absent at this time of year without causing major disruption to our teaching responsibilities. If we were to attend, we could only stay a very short time, barely enough to meet the Swedish scientists.

Moreover, Mrs. Curie was ill this summer and has not fully recovered. I am therefore requesting that our trip and the lecture be postponed to a later date. We could, for example, come to Stockholm at Easter or, even better, around mid-June… 2”

The Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded for only the third time, is one of five prizes granted annually, as per the will of its creator Alfred Nobel, to reward “those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.”3 Alfred Nobel (1833–1897), a Swedish chemist, conducted research on explosives and pioneered technical innovations (notably, transforming unstable nitroglycerin into safely transportable dynamite), building an industrial empire in chemicals and oil. In his will, he created a foundation to endow five generously funded prizes.

The Nobel Prizes in Physics and Chemistry are awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to the authors of the “most important discovery or invention” in their respective fields. Three other prizes are also awarded: one by the Karolinska Institute for Physiology or Medicine, one by the Swedish Academy for the “most outstanding literary work of idealistic inspiration”, and one by a committee appointed by the Norwegian Parliament to honor “the person who has done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.”4

he Swedish and Norwegian institutions designated by Nobel established committees to manage prize selection. These committees receive nominations from eligible individuals — usually members of academic societies or foreign academies. The committees assess the nominations and produce reports justifying the selections. In 1903, the Nobel Committee for Physics was chaired by Professor C.-B. Hasselberg, and included Robert T. Thalén (former physics professor at Uppsala), Hugo H. Hildebrandsson (meteorology professor), Knut J. Ångström (physics professor in Uppsala), and Svante Arrhenius (physics professor in Stockholm).

In 1901, the first Nobel Prizes in science were awarded to W.C. Röntgen for the discovery of X-rays (physics), and to Van’t Hoff for chemical kinetics and osmotic pressure (chemistry). In 1902, H.A. Lorentz and P. Zeeman were honored for their work on magnetism’s influence on radiation (Zeeman effect), and Emil Fischer for research in sugar synthesis and organic compounds.

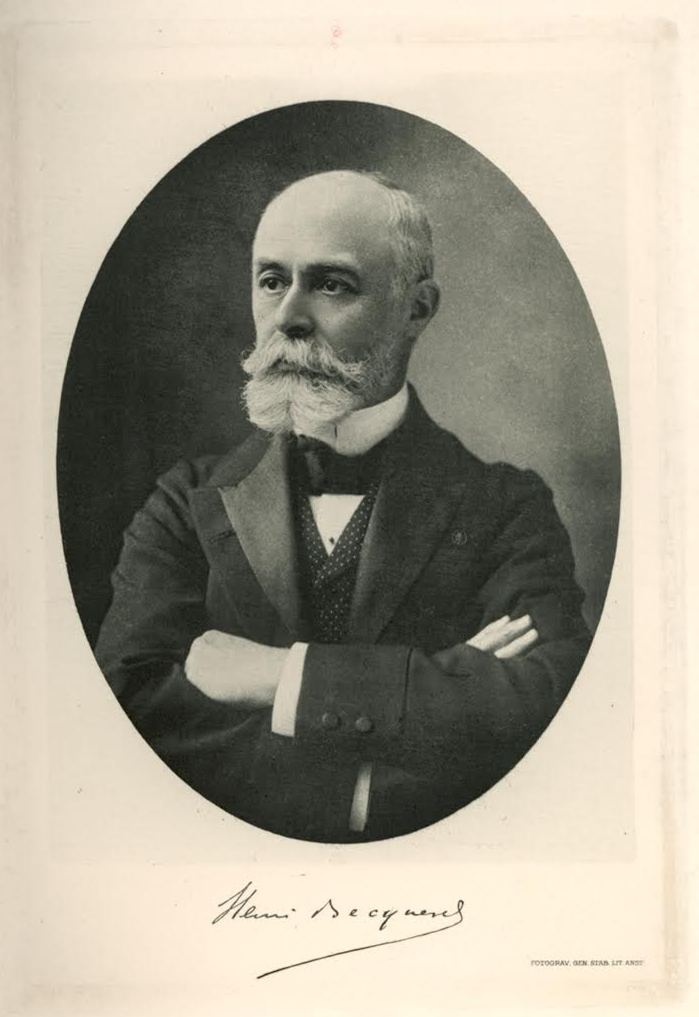

In 1903, the Physics Committee agreed it was time to honor the pioneers of radioactivity, the most significant recent discovery. The first names proposed were Henri Becquerel and Pierre Curie, either separately or jointly, by members of the Paris Academy of Sciences, including Gaston Darboux, Henri Poincaré, Gabriel Lippmann, and Eleuthère Mascart5. Initially, Marie Curie’s candidacy was apparently not considered, prompting intervention by Gösta Mittag-Leffler, a highly influential Swedish mathematician, although not a Nobel committee member. A supporter of women in science, Mittag-Leffler wrote to Pierre Curie (unofficially) to inform him he was being considered for the Nobel Prize.

In his response, Pierre Curie insisted the prize be shared with Marie:

“You kindly informed me that I was being considered for the Nobel Prize,” Pierre wrote on August 6, 1903. “I don’t know how credible that rumor is, but if there is any truth to it, I would very much like to be considered jointly with Mrs. Curie for our work on radioactive bodies. Her initial research led to the discovery of new elements, and she played a major role in it (she also determined radium’s atomic weight). I think separating us in this matter would surprise many. Besides, wouldn’t it be more artistically pleasing to keep us associated?

Of course, I would not presume to approach any commission member directly. But if you do find an opportunity to share my view, I would be grateful. I have sent Mrs. Curie’s thesis to Sweden, and I trust they will recognize her equal contribution.

Needless to say, I have no expectations about this prize, and I would feel no disappointment if we don’t receive it, but one must consider all possibilities.

Thank you again for your kindness. Yours sincerely…”6

There was a problem: Marie had not been nominated for that year, which was required for selection. However, thanks to a prior nomination submitted the year before by Professor Charles Bouchard of the Paris Faculty of Medicine (and a corresponding member of the Stockholm Academy), Marie’s candidacy was accepted.

Some members of the Physics Committee even considered awarding the prize solely to the Curies. On September 8, 1903, Mittag-Leffler wrote to Henri Poincaré to ask “whether it would be more just to award the Nobel Prize in Physics to Mr. and Mrs. Curie, or to split it between Becquerel and the Curies.”

On September 12, Poincaré replied that he believed “it would be fairer to share the prize between Becquerel and the Curies, since while the Curies are more precise and advanced, Becquerel was the initiator.” He added pragmatically, “But I mostly want the plan to succeed, and we shouldn’t insist on the division if that insistence jeopardizes it.”7

After long discussions and much negotiation, the Physics Committee proposed to share the prize between Henri Becquerel and the Curies. The Curies’ discovery of radium was not mentioned, at the request of the Chemistry Committee, which viewed radioactivity as part of their field — reserving the possibility of a future Chemistry Prize, which Marie would indeed receive in 1911.

On November 12, 1903, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics to Henri Becquerel, for the discovery of spontaneous radioactivity, and to Pierre and Marie Curie for their research on the radiation phenomena discovered by Becquerel. The Chemistry Prize was awarded to Svante Arrhenius for his theory of electrolyte dissociation. In accordance with the Nobel statutes, the awards were formally presented on December 10, the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death. Of the three French laureates, only Henri Becquerel was present in Stockholm.

In his speech, Academy President H.-R. Törnebladh praised the laureates’ work and concluded:

“The discoveries of Mr. Becquerel and Mr. and Mrs. Curie are intimately linked; the latter two have worked together. The Royal Academy of Sciences therefore did not wish to separate these eminent scientists in awarding the Nobel Prize for the discovery of spontaneous radioactivity. The Academy found it fair to divide the 1903 Nobel Prize for Physics, granting one half to Professor Henri Becquerel and the other to Mr. and Mrs. Curie for their outstanding contributions to the study of the rays discovered by Mr. Becquerel.” Addressing Henri Becquerel, he continued: “Your brilliant discovery of radioactivity demonstrates the triumph of human science, which explores nature by projecting the undistorted rays of genius across vast frontiers. Your victory, sir, is a brilliant refutation of the old phrase ignoramus — ignorabimus, and it fuels the hope that scientific labor will continue to conquer new domains — a vital hope for humanity.”

Finally, addressing the French government representative, who received the prize in the Curies’ absence, he declared:

“The great success of Mr. and Mrs. Curie gives new meaning to the divine words: ‘It is not good for man to be alone; I will make him a helpmate fit for him.’ But more than that, these scholarly spouses also represent the union of different nationalities — a hopeful sign for humankind’s collective efforts toward scientific advancement. Although we deeply regret their absence due to professional commitments, we are pleased to present the prize to France’s distinguished representative, Minister Marchand, who has graciously agreed to accept it on their behalf.”

- Eve Curie, Madame Curie, Gallimard, 1938, p. 290. ↩︎ ↩︎

- Eve Curie, ibid., p. 291. ↩︎

- “Statutes of the Nobel Foundation,” published by Elisabeth Crawford, The Founding of the Scientific Nobel Prizes (1901–1915), French translation by Nicole Dhombres, Belin, 1988. (Unless otherwise noted, the following quotations are taken from this work). ↩︎

- “Statutes of the Nobel Foundation,” ibid. ↩︎

- On the awarding of the Nobel Prizes, networks of influence, and decision-making processes… see Elisabeth Crawford, ibid., and Girolamo Ramunni, “Nobel Prizes: The Weight of Political Criteria,” La Recherche, no. 148, 1984, p. 1256, and Elisabeth Crawford, “Nobel Prizes and Politics,” La Recherche, no. 151, 1984, p. 130. ↩︎

- Letter from Pierre Curie to Gösta Mittag-Leffler, Mittag-Leffler Institute. (A copy is kept in the Archives of the French Academy of Sciences, Paris). ↩︎

- Letters exchanged between Henri Poincaré and Gösta Mittag-Leffler, Mittag-Leffler Institute. ↩︎